- Home

- Kabir, Nasreen Munni

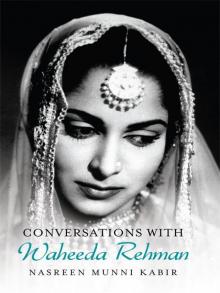

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman Page 2

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman Read online

Page 2

NMK: How did he first hear of you?

WR: He was sitting in a distributor’s office when they heard a commotion outside—the distributor’s name escapes me now—but I think he distributed Mr & Mrs ’55 in Hyderabad. Guruduttji asked him if there was some trouble on the street and he was told the stars of a popular Telugu film were passing by and it was the excited fans that were making the commotion.

The distributor then added: ‘A new girl has performed a song in the film. It has caused a sensation. When the stars go on to the stage, the audience demands to see this young girl. Her name is Waheeda Rehman.’ Guruduttji was surprised: ‘Waheeda Rehman? That’s a Muslim name. Does she speak Urdu?’

‘I hear she also speaks Telugu and Tamil. She came wearing a gharaara and thanked the audience in Urdu at a function where they were celebrating the success of Rojulu Marayi.’

Following the success of Rojulu Marayi, Waheeda Rehman acted in three other south Indian productions. Aged seventeen. Madras, 1955. Photograph: M.A. Mohan.

That’s when Guruduttji told the distributor he would like to meet me because he was looking for new actors to cast in his next production.

The distributor then called Mr Prasad to set up a meeting. Mr Prasad had not heard of Guruduttji. Very few people in the south had heard of him in the mid-fifties. I think there weren’t many film magazines at the time and in any case no one in my family read them, so we were unaware of his name.

The distributor explained to Mr Prasad that his friend was a well-known Bombay director and had made a number of successful films. Then Mr Prasad called my mother and told us that Guruduttji wanted to meet me. My mother and I made our way to the distributor’s office the next day. I think the meeting lasted about half an hour. Guruduttji hardly spoke. He asked us a few questions in Hindi: where we were from, etc. That was it.

We went back to the hotel where we were staying in Hyderabad. When Mr Prasad asked about the meeting, my mother commented that Guruduttji said very little. Mr Prasad said some people were just made like that. We returned home to Madras a few days later.

NMK: Before Guru Dutt met you, had he seen Rojulu Marayi?

I say this because I am sure he would have been struck by the sparkling impression you made on the screen.

WR: No, he hadn’t seen the film. He had no idea what I looked like on camera. He heard my name and asked to meet me without having seen me at all. There was no reason why the distributor had to mention me in the first place. So how could I not believe it was destiny?

After our first meeting in Hyderabad, three months went by and then someone—I believe his name was Manubhai Patel—came to see us at our home in Madras. He said he was from Bombay. I think he was a film distributor. He said he had come on behalf of the director whom we had met in Hyderabad. Of course, by that time, we had even forgotten Guruduttji’s name, to which our visitor said: ‘Well, Guru Dutt has asked me to take you to Bombay. He wants to sign you.’

My mother was most surprised and decided to discuss the idea with her friends. They advised her to say Bismillah and go. She was very reluctant. Bombay was like a foreign country to us. As usual she asked Mr Prasad for his advice and he said: ‘Go, Mrs Rehman. There’s no harm if she works in Bombay, but remember she is not a slave. Don’t agree to all their demands. If you don’t agree to something, say it. If you don’t like living there, come back. Just don’t get intimidated.’

So the three of us—my mother, a family friend who was called Mr Lingam and I—landed in Bombay at the end of 1955. We stayed at the Ritz Hotel in Churchgate.

NMK: Did you audition? Or take a camera test?

WR: No audition or camera test. But they took some stills and then the time came to sign the contract. There were a number of people at the meeting—director Raj Khosla who was making C.I.D., in which I was supposed to be cast; production-in-charge S. Guruswamy; cameraman V.K. Murthy, who didn’t say much; chief assistant Niranjan and Guruduttji. The meeting was held at Guruduttji’s office on the first floor of Famous Studio in Mahalaxmi. Famous had two shooting floors and some offices on an upper floor that were rented to different production companies, including Guru Dutt Films.

One of the first things Raj Khosla said was that my name was too long. It had to be changed. I said: ‘My parents have given me this name and I like it. I won’t change it.’ Pin-drop silence. Raj Khosla got all het up. He was a Punjabi, you know, and they can get all excited. He said: ‘Your name is too long. “Waheeda Rehman.” Who will say all that? We will call you “Waheeda”, and drop the “Rehman”. If you don’t like it, change your name. It’s common practice for actors to have screen names. Dilip Kumar’s real name is Yusuf Khan, Meena Kumari is Mahjabeen Bano, Madhubala is Mumtaz Jahan and Nargis is Fatima. Everyone has changed their names.’

I said: ‘I am not everyone.’

NMK: You said that?

WR: Yes. [laughs]

I don’t know how I had the courage, but I didn’t stop there and added: ‘I have done two Telugu and two Tamil films and did not need to change my name. I haven’t run away from home, nor am I hiding from my family. My mother is sitting right here. I am not sure why I should change my name.’

Guruduttji had this habit of sitting with his hand under his chin and his elbow resting on a table. He listened quietly. I was told they needed time to think it over. We stayed on in Bombay for an extra week because my name had become the sticking point.

NMK: I think you were among the first generation of Muslim actresses, post 1950s, who did not adopt a screen name—which was most often a Hindu name. As we know Meena Kumari, Madhubala and Nargis did not use their real names.

WR: Many actors had screen names. I think they wanted my name changed because they didn’t think it was sexy. I don’t think it was more than that.

I remember every detail of that day. Guruduttji sat without saying a word while Raj Khosla was jumping in and out of his seat.

NMK: Did they suggest any alternative name to you?

WR: They said they’d have to think of one. It was finally agreed at the next meeting that I could keep my own name. They asked my mother to go ahead and sign the contract. I could not sign because I was under eighteen.

Just before she could put pen to paper, I asked her to wait a minute and said: ‘I’d like to add something to the contract.’ Raj Khosla was surprised: ‘Newcomers don’t usually make demands. Just sign.’ Guruduttji kept silent. Then I told them if I did not like any costumes, I would not wear them. Guruduttji sat up. I am sure he must have thought to himself—here’s this girl, not old enough to sign her own contract, and just look at her nerve. [we laugh]

Then he said in his quiet voice: ‘I don’t make films of that kind. Have you seen any of my films?’

‘No.’

‘All right. Mr & Mrs ’55 is running in town. Go and see it. We’ll talk about the costumes later.’

We were given cinema tickets and we went to see Mr & Mrs ’55 at Swastik Cinema on Lamington Road. The following day we returned to the office. We said there was nothing wrong with the costumes. Madhubala wore sleeveless blouses in the film, but sleeveless blouses were commonplace by then. But I said I still wanted the clause about costumes added. Raj Khosla looked at Guruduttji and said: ‘This is amazing, Guru. You’re listening to this girl and not saying anything. The choice of costumes depends on the scene and not on the actress.’

I can’t believe I was so outspoken, but I insisted: ‘When I am older, I might decide to wear a swimsuit. I won’t now because I am very shy.’ Raj Khosla retorted: ‘If you’re so shy, why do you want to work in films?’ I said calmly: ‘I haven’t come here of my own accord. You called us.’

No decision was made. We were driven back to the Ritz Hotel. The next day we went back to the office. The clause about my costumes was added and my mother signed my three-year contract with Guru Dutt Films.

NMK: You were amazingly forthright for someone so young. In the 1950s one could not imagine that women could so

boldly voice their wishes. And there you and your mother were, arguing about contract clauses without the backing of anyone in the Bombay film industry. You were virtually outsiders to that world.

WR: When my father was on his deathbed, he told us all: ‘Fear no one but God. Behave decently and respect your elders. But do not fear anyone.’ Maybe those words stayed with me. I was keen to work in films, but I was not dying to.

NMK: It sounds like you were always a confident person.

WR: I think it was because I lost my parents when I was very young. As I mentioned to you, my father died in 1951 when I was thirteen, and I saw my mother somehow manage to make ends meet. Those experiences probably made me strong. I don’t know.

Life is full of ups and downs. I have always prayed to God to give me the courage to face problems and not feel defeated.

NMK: Does your faith come from a religious education you had in your childhood?

WR: There was no maulvi saab who came to the house to teach us the Quran Shareef. That was the tradition in many Muslim families. It was my mother who taught us how to pray. My father prayed and kept all the fasts during Ramzan, even though he had to travel about in the heat.

My parents encouraged us to live as Muslims, but they were very broad-minded and liberal. Yet certainly we sisters knew we could not cross the line.

NMK: What do you remember of your parents?

WR: They were a wonderful couple. My father was a district commissioner. His name was Mohammed Abdur Rehman and my mother was Mumtaz Begum. She used to wear printed georgette sarees—they were the fashion in those days. Their faces are distinct in my mind, but I cannot recall their voices. I used to call my parents ‘Mummy’ and ‘Daddy’.

My parents believed the most important thing in life was being a good person. My father often said: ‘No one has seen hell or heaven. Whatever we have is here—in this life. You must get on with people and be compassionate.’

NMK: You showed me a photograph of your parents. I can see a close resemblance between you and your mother.

WR: My sisters Shahida and Sayeeda look a lot like her too. My eldest sister Zahida looks more like my father who had Tamilian features. I have the same nose as my father.

My maternal grandfather was a tall, fair-skinned man who worked in the police department. Everyone in my mother’s family was light-skinned. They were originally from north India—and their ancestors probably came from Afghanistan or Iran. Usually Muslims in the south aren’t as fair.

NMK: Did you have a large extended family?

WR: We grew up with many maternal uncles and aunts because my mother had five sisters and four brothers. I don’t remember seeing anyone from my father’s side. I knew my paternal grandfather was a well-to-do landowner. When my father was born, his mother passed away.

My father used to tell us how keen he was on studying. As a young boy, he would shut himself in his room and put out all the lights. When everyone assumed he was sleeping, he would sneak out of his room through a window and sit under a street lamp and read.

People asked him why he wanted to study—after all he was the son of a rich zamindar and, instead of studying, he should look after the estate like his father had done before him. They told him he could live like a king, but my father was firm: ‘I don’t want to live like a king. I want to study.’ That caused a lot of friction, and when my grandfather remarried he left the family home and settled in Madras.

Father passed the IAS [Indian Administrative Service] exam and finally became a district commissioner sometime in the 1930s. It was through his friends that his marriage was arranged in the late 1920s. My parents had not seen each other before they got married. After all we’re talking about a time that’s almost a century ago now. That’s how it was in those days.

NMK: Was your mother educated?

WR: Not formally, but she was very intelligent. She was an aware kind of person, and mostly self-taught. I remember she used to read the Illustrated Weekly, a popular English-language magazine, and the Urdu edition of the Reader’s Digest. Since my father was a progressive and modern man, she learned how to play tennis and cards, which was quite unusual for women of her generation.

Most of my childhood was spent in Andhra Pradesh, which was a part of the Madras Presidency then. They were happy times. My father and his friends went deer hunting and the rest of the family went on picnics. We children were given the task of gathering twigs and stones to make a fire for cooking. We were always having parties at home. Because there were only girls in our home, my parents did not want to employ a live-in male cook, and as a result my mother did all the cooking. She was always busy.

NMK: It sounds like you had an idyllic childhood. Did you study in an English-medium school?

WR: Yes. My mother spoke Urdu well and she wanted us to learn how to read and write Urdu. It wasn’t easy finding an Urdu teacher in the south, so she taught us herself. But we sisters would dream up some excuse or the other to avoid studying. I did not learn Urdu as well as I should have. I can read but I read slowly.

My father was posted all over south India, so we managed to pick up some of the local languages. I am not very fluent in Tamil and Telugu, but I can get by. You don’t easily forget what you learn in your childhood.

NMK: What is your earliest memory?

WR: I have many. But one that stands out?

I must have been about four or five years old. My father was posted to Palghat, which is now called Palakkad. It’s in Kerala. During the Onam festival we went to the Palghat Fort to watch the procession of decorated elephants. We stood on the parapet and my father lifted me high in his arms so I could see the elephants through the opening in the fort wall. The image of those beautifully adorned elephants is still clear in my mind.

Like a fool I told my father that I wanted to own an elephant. He said: ‘Darling, it’s not possible. An elephant is a big animal; you can’t keep an elephant as a pet.’ ‘What about a baby elephant?’ He patiently explained that the baby elephant would grow up into a big elephant.

I remember another occasion—in Nagapattinam in Tamil Nadu, a mahout would ride his elephant through our neighbourhood and stop at each house. When they came to our place, we would give the elephant a coconut. It was very smart and would crush the coconut and scoop up the white coconut flesh with its trunk. Animals and birds have fascinated me from a young age.

NMK: Was going to the movies part of your growing-up years?

WR: We saw many films. My parents were fond of music and also enjoyed going to concerts and dance recitals.

Hindi films played in the south a few months after their release, and I believe the first film I saw was Zeenat with Noorjehan and Yakub. I must have been about eight years old. How we cried when one of the heroes died! My mother tried consoling us: ‘This is all make-believe. He didn’t really die.’ But we continued wailing in the cinema hall. She tried desperately to quieten us down because everyone was staring at us. She was very embarrassed.

I saw Barsaat and Dastan when I was about ten. And there was this film with Dev and Madhubala. I don’t remember the title. It had a lovely song in it: ‘Mehfil mein jal uthi shama parwaane ke liye’.

NMK: It’s a song from Nirala, a 1950 movie.

WR: Nirala? That’s right.

NMK: And Hollywood movies? Which ones did you see?

WR: Gone with the Wind. There were other films, but I can’t remember them now. My parents always made sure the films we saw were suitable for us girls. But more than going to the cinema, our main entertainment was going on picnics.

NMK: I am curious to know if you were influenced by any Hollywood actress when you came to act in films.

WR: I liked Ingrid Bergman very much. You could never forget her presence on the screen. I liked Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind.

I never wanted to copy any of the Hollywood actresses, and did not think I should perform in the way they did because no one could. Hollywood productions are totally different from o

urs. How could I do a scene in Guide or Dil Diya Dard Liya with Vivien Leigh in mind?

I have always believed you should do what you feel is right. I never think: ‘Nasreen sits like this so I should sit like her.’ You can’t imitate anyone.

NMK: You talked about going on picnics as a family. How many sisters are you?

WR: Four. The eldest is Zahida and we call her ‘Bi-Apa’. Then there’s Shahida, or ‘Sha-Apa’, and Sayeeda and I. All our names end in ‘da’.

When we were growing up, some people commented to my father: ‘Rehman, isn’t it a pity that God did not give you a son?’ He would say: ‘Emperor Akbar had nine jewels in his court and I have four.’

I used to get cross when I heard people talk like that. So what if we did not have a brother? I was sure us girls would do well in life.

Accompanying her father on an official tour (L to R), young Waheeda, M.A. Rehman, Mumtaz Begum and sister Sayeeda. Circa 1949.

I once told my father: ‘Daddy, don’t worry, one day my photograph will appear in the papers. I don’t know why, but it will.’ I also told him I would own a farm and, many years later, I did. Can you believe that?

NMK: Were these the kind of daydreams you had?

WR: Yes. I had a feeling I was going to make something of my life, even when I was ten years old. But I was a sickly child. I had a kind of allergic asthma and every few months I’d fall ill. My parents were very worried about me and did not know if I would survive. For a while I would be all right and then fall sick again because we kept moving home.

When my father was posted to another city, he usually went on ahead while my mother would arrange for the house to be painted and cleaned before we joined him. She used to call my father ‘Saab’, and she would say: ‘Saab, as soon as you get there, make sure you find a doctor.’ She knew I would need a doctor soon enough.

Drinking different kinds of water, the smell of paint, the dust and the new environment would set off an allergic reaction in me. Recuperating from these bouts of illness took time and this meant my schooling suffered a great deal. I was a fairly good student but a slow learner. I can’t say I’m very educated in that sense.

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman