- Home

- Kabir, Nasreen Munni

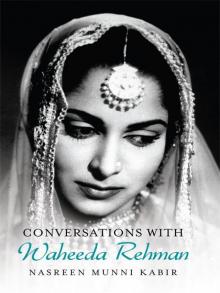

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman Read online

NASREEN MUNNI KABIR AND WAHEEDA REHMAN

Conversations with

Waheeda Rehman

Contents

Dedication

Encounters with Waheeda Rehman

Conversations

Appendix: Filmography

Follow Penguin

Copyright

This book is dedicated to my wonderful parents who taught me the meaning of compassion and integrity.

Encounters with Waheeda Rehman

When I was researching the life of Guru Dutt—which ultimately resulted in two books and a documentary made in 1989 for Channel 4 TV, UK, called In Search of Guru Dutt—I was naturally very keen to meet Waheeda Rehman. No story about Guru Dutt would have been complete without her speaking of him. She is such a vital presence in his work that when you meet Guru Dutt’s fans, you realize that half are in love with him and the other half are in love with her.

Finding a way to meet Waheeda Rehman for my documentary was at the top of my list of priorities. Every time I came to Bombay from London in 1987, I’d try calling her. This was long before mobile phones existed, and getting to speak to a star meant going through a bevy of domestics who answered the phone, all sounding as though they had graduated from the same charm school: ‘Madam is not here—call next week—madam is out.’

Out? Out of town?

‘Bahar gaon gayin hai’ [literally translates as ‘gone to a village abroad’].

Considering the many calls they take from total unknowns, brushing off yet another stranger must become second nature.

In the middle of 1988, I managed to speak to Waheeda Rehman at last. I explained the reason for my calls and she agreed that I could come and see her the next day, but why a documentary on Guru Dutt? For whom? What would it say? Her hesitation was to be expected because documentaries on Indian film practitioners were rare in those days, and certainly none I knew of were made for a British broadcaster.

The next day I made my way to her house on Bandstand in Bandra. Though her sprawling and gorgeous ground-floor apartment had been rented out, a large room was sectioned off where she stayed during her visits from Bangalore. When Waheeda Rehman opened the door, I was overwhelmed by images of her lifelike screen characters—Gulaabo, Shanti and Rosie. Waheeda Rehman has had such an emotional impact on us all that it took a few minutes for the sheer excitement to settle. Then I explained the purpose of my documentary was to gain insight into Guru Dutt’s life and films by recording all the people who had worked alongside him. At that first encounter, Waheedaji was gracious and attentive but not over-friendly—I later realized she is in essence a reserved person. At the end of our hour-long meeting, she agreed to the film interview and we parted.

In Search of Guru Dutt, the documentary, was made later than expected, but Waheeda Rehman had said yes, and, unlike many film stars who make promises they later break, she kept her word and arrived at a friend’s flat in Khar where the interview was shot. Waheeda Rehman spoke with life and enthusiasm about the days when she worked with Guru Dutt. She got so involved with that past time that, at one point, she even spoke of him in the present rather than the past tense. During the filmed interview (and in this book) she always referred to him as ‘Guruduttji’, in deference to his real name. His full name, Gurudutt Shivshanker Padukone, was in fact shortened to Guru Dutt, causing many to assume (and continue to assume) that, since his surname was Dutt, he must be a Bengali rather than a Bangalorean.

I met Waheedaji again in 1990 to film an interview on Lata Mangeshkar, who insisted that this fine actress be part of the documentary I was then making on this great playback singer.

Over the next fifteen years, I met Waheedaji occasionally and gradually got to know her. I found her personal story absorbing. Her father, Mohammed Abdur Rehman, a district commissioner, was from Tamil Nadu. As a young man, he broke with tradition by moving away from his landowning family, preferring to make his life as a bureaucrat rather than live as a rich zamindar. Though not formally educated, her mother, Mumtaz Begum, was by all accounts a woman way ahead of her times. The youngest of four daughters, Waheeda Rehman was a sickly child, suffering from severe asthma. When she was thirteen, her father suddenly passed away and her mother had to somehow make ends meet. Young Waheeda and her sister Sayeeda, both trained in classical dance, performed on the stage, but they earned very little.

Then life changed dramatically for young Waheeda when she accepted a dancing role in the Telugu film, Rojulu Marayi. Her sparkling screen presence immediately caught the attention of the audience who instantly fell for her. Her success in the film ultimately led to a meeting with Guru Dutt in Hyderabad. Three months after their fortuitous meeting, in 1955, the seventeen-year-old Waheeda Rehman moved to Bombay where she signed a three-year contract with Guru Dutt Films. The release of C.I.D. and Pyaasa brought further fame and recognition and, by the end of the 1950s, she was counted among the leading stars of Hindi cinema.

Waheeda Rehman’s success was not limited to her performances in Guru Dutt’s films. Her subtle screen presence and exceptional dancing talent enchanted the audience. Her natural acting style and willingness to accept atypical roles soon brought her to the attention of India’s finest directors. She continued over the years to bring dignity to her characters and substance to her roles, evident in many key films, including Mujhe Jeene Do, Abhijan, Guide, Teesri Kasam, Reshma Aur Shera and Khamoshi. Even in less memorable productions, Waheeda Rehman made a lasting impression.

In 1974, she married actor Kamaljeet Rekhy. When they became parents to a son and a daughter, they chose to make Bangalore their home, living there on a farm for some sixteen years. Waheeda Rehman stayed away from films, only to return to the screen in the late 1980s, this time in mother roles. But her absence did not diminish the respect and admiration she has won from audiences across generations. Even today, the eyes of her admirers light up when speaking of her.

Besides her personal story, details of which aren’t widely known, there is so much cinema history linked to her life that I believed it was important to record her experiences. When I first asked her, sometime in 2005, about writing a book on her, she smilingly said no. Later she revealed to me that she has this habit of saying no at first, even when a film role was offered. Her initial reluctance to the idea of a book came from wondering why her story would interest anyone in the first place. She did not say this for effect. Her humility is genuine. In spite of her great fame, and the countless awards that she has won, including the prestigious Padma Bhushan in 2011, she remains a deeply modest person at heart. In fact she still does not believe that her enduring fame has anything to do with her natural talent, but attributes it all to just being lucky.

Despite her reluctance, I persisted, and made it a point to give her the books I did with others, including Lata Mangeshkar and Gulzar. I wanted her to see that the format of an in-depth conversation might work well and encourage a direct connection with the reader, as she would be sharing her story in her own voice and words. I had almost given up persuading her when, in the summer of 2012, she came to London for a holiday with her friend Barota Malhotra and finally said yes during a meal we were having in Colbeh, a famous Iranian restaurant off Edgware Road.

Between December 2012 and November 2013, we met over twenty-five times in her Bandra home. Our conversations in Hindustani and English were recorded and later transcribed. As many of the film references and times relate to a period prior to 1995, when Bombay was renamed Mumbai, prior to 2001, when Calcutta became Kolkata, and before Madras became Chennai in 1996, I have used the original names of the cities for consistency.

Each of our s

essions would last for about two hours. After a few weeks, a relaxed and easy routine set in. I’d ring the doorbell at Sahil, her home in Bombay, and a domestic would open the door and show me into an expansive living room that overlooked the sea—a most gorgeous room dominated by a striking portrait of Waheeda Rehman by M.R. Achrekar. From the living room, I was led to the dining area where I’d set up my MacBook Pro and digital recorder. A minute or two later, Waheedaji walked in, wearing a simple and elegant salwar kameez, smiled warmly, ordered me a nimbu-paani and then we settled down to talk. Her discipline and respect for work showed—she never took calls or sent text messages or allowed anything to interrupt the conversation. Her concentration and attention was total. When lunchtime approached, she would invariably ask me to join her for lunch. Her tehzeeb and refined upbringing were always in evidence.

What I discovered about Waheeda Rehman was that she is a feisty lady and has always fought her corner, even from a young age. Besides her confidence and intuitive understanding of right and wrong, she also has a natural gift for storytelling. Admittedly, it takes her time and a sense of trust and ease to open up, but when she does, she comes alive. Her descriptions of the past and the people she knew have a once-upon-a-time feel to them—every event is told with a beginning, middle and end. She has a great memory and gets so involved in evoking the past that her eyes sparkle—it’s as though she were seeing actual images of that lived experience. In addition to her lively conversation, her insight into the craft of film-making shows a keen and alert intelligence, allowing this book to hopefully serve as an important chronicle of a great era in Indian cinema.

Getting to know the genuine person behind her illustrious reputation, great beauty and winning smile has been a wonderful privilege. Waheeda Rehman is truly as lovely in real life as she is on the screen.

Nasreen Munni Kabir

My thanks to Sohail Rekhy, Kashvi Rekhy, Arun Dutt, Peter Chappell, Shonali Gajwani, M.A. Mohan, Priya Kumar, Shameem Kabir, Anjelina Rodrigues, Subhash Chheda and the team at Penguin Books India.

Conversations

WR: My father died in 1951 and for some years after that I saw my mother struggle to make ends meet. The social status, the cars and the houses had gone with his passing and we were left with nothing.

When I turned seventeen, my mother became worried about my future and thought if I were to get married, I might have a more secure life. I didn’t want to get married and preferred the idea of working. But what could I do? I didn’t have much of an education, so how was I supposed to find a job? It was around that time that the producer C.V. Ramakrishna Prasad, who had known my father, called out of the blue and offered me a dancing role in the Telugu film Rojulu Marayi. When I heard about his offer, I jumped with joy and told my mother: ‘It is God’s wish! Please let me do it.’

My mother immediately curbed my enthusiasm and said it was not a good idea. She thought I was just too young to work in films. She was probably afraid of what people might say, as there used to be a lot of social stigma attached to girls working in cinema in those days. When my father was alive, she could face any sort of criticism, but without his support how would she manage? So she refused Mr Prasad’s offer.

But Mr Prasad was a persuasive man. He called back and reassured her: ‘Mrs Rehman, I know you come from a decent family, but times have changed. Film acting is as honourable a profession as any other. Your daughter is like a daughter to me and I am producing this film. You can accompany her to the studios and need not leave her side. She has danced on the stage. Where’s the harm in her dancing in a film?’

My mother thought about it for a few days and finally agreed. We were living in Vijayawada and because the film was going to be made in Madras, we moved there.

NMK: The dance and song you performed in the 1955 film Rojulu Marayi, ‘Eruvaka sagaro ranno chinnannaa’, became all the rage. I watched the song on YouTube. You have such natural elegance that it is not surprising everyone took notice of you.

WR: I can’t tell you how people loved that song. Master Venu composed it and it had a lovely rhythm.

In those days, audiences were known to throw coins at the screen to show their appreciation and that’s what people did when my dance started. We were told that when the film was over, people would ask the projectionist to run the song again. My mother couldn’t believe it and went to a cinema hall to see for herself—she discovered it was true.

Rojulu Marayi means ‘days have changed’ and the title perfectly described that moment in my life.

NMK: For a young girl who had no idea of film studios, or how films were made, what was it like facing the camera for the first time? Was the whole process of film-making daunting?

WR: Akkineni Nageswara Rao, Nagarjuna’s father, and Shavukar Janaki were the lead stars of the film and I appeared in this one dance scene.

Everything was new to me. I didn’t know what to expect. The director Thapi Chanakya helped me get over my nervousness by saying: ‘When the assistant holds the clapperboard in front of you to announce the take, pay no attention to it. Don’t get nervous. People think they must do something when the take is announced and the camera is rolling—there’s nothing you need do. What you’re doing is fine.’ The director’s father was the famous Telugu writer Thapi Dharma Rao who wrote the dialogue for Rojulu Marayi.

I remember when I was dancing I kept looking down at my feet because I was very conscious of my uneven, funny-looking toes. People in the south use the term ‘Amma’ with affection and so Akkineni Nageswara Rao told me gently between takes: ‘Amma, don’t look down. Look at the camera. You don’t have a bad face.’

NMK: Do you remember how long the song took to be completed?

WR: I think it took four or five days. Did you know that a Bombay music director copied that Rojulu Marayi song? And guess who? S.D. Burman!

Sometime in the late 1950s, I got a call from Dada: ‘You know that Telugu song of yours? Well, sing it for me.’

‘Dada, how can I? I am not a singer.’

‘I am not going to record you. I know you’re not Lata Mangeshkar. Go on, sing!’

I sang it for Dada a couple of times and he composed a song with the same tune for Bombai Ka Babu. [sings] ‘Dekhne mein bholaa hai dil ka salonaa, Bambai se aaya hai babu chinnannaa.’ Majrooh Sultanpuri wrote the lyrics and even used the word ‘chinnannaa’ from the original.

Some years later the composer Ravi asked me to sing him the same song because he wanted to rework the tune for a Hindi film as well—I don’t remember which film. I told him Burmanda had already used the tune, but Raviji insisted I sing it for him. He thought the song had a beautiful melody.

NMK: The success of Rojulu Marayi led to your working in other films in the south. Can you remind us of which ones they were?

WR: The next Telugu film I worked in was Jayasimha, in which I played a princess. N.T. Rama Rao was the hero of the film and he was a big star, but did not talk much. Anjali Devi, the heroine of Jayasimha, was very friendly with me and told me not to worry. She said he was a reserved man, that’s all.

We had to reshoot my ‘Eruvaka sagaro . . .’ song for the Tamil version of Rojulu Marayi, which was called Kaalam Mari Pochu and starred Gemini Ganesan. Then I had a dance scene in Alibabavum 40 Thirudargalum [Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves], a Tamil film with M.G. Ramachandran in the lead.

I was lucky to have worked with all the leading stars of south India, including M.G. Ramachandran, Gemini Ganesan and N.T. Rama Rao.

NMK: What was it like making films in Madras in the 1950s?

WR: Films were made in a very professional manner. If the call sheet had a start time of nine in the morning, all the actors were there on the dot. I remember there was an excellent Bengali make-up artist who was living in Madras, and the stars would go to his house at six in the morning, have their make-up done and then come to the set at nine, ready to shoot. South Indian actors had a tremendous sense of discipline.

The way of working was differ

ent there. If an actor did not behave professionally, or was continuously late for work, no matter how important he or she was—and I have seen this with my own eyes—producers like S.S. Vasan or B. Nagi Reddy would throw them out. Not just from the film in which they were starring, but from the industry.

Aged fifteen. Madras, 1953. Photograph: M.A. Mohan.

NMK: It sounds like the directors and producers had more clout than the stars.

WR: Yes, they did. Most south Indian films were made within three or four months, and I believe still are, while it sometimes took years for a film to be completed in Bombay. Things have improved a lot. The younger generation of directors today finish a film within a year.

When I began working in Hindi cinema I found films were made in a relaxed—I’d say even slack—way, as compared to the south. In Bombay, the stars came to the set in their own sweet time. When I was shooting for my first Hindi film, I arrived at the studio at eight and was ready to shoot by 9.30. But then I had to sit and wait for Dev Anand who arrived at eleven.

Though I must tell you that if we needed to work late into the evening—because the set was going to be dismantled or something—Dev always agreed to work late. But he never came on time.

NMK: The Rojulu Marayi song opened many doors for you and led to your meeting Guru Dutt.

WR: That’s right. The film was such a big hit. The cast was invited all around Andhra to celebrate its success and at the end of the tour we arrived in Hyderabad. That’s where I met Guruduttji for the first time.

I am a great believer in destiny. Even though Guruduttji did not have the faintest idea who I was, he asked to meet me—a newcomer. It felt like something out of the ordinary—it had to be destiny.

Many good things have happened to me. I never planned anything. Nor did I manipulate or calculate. Yet good things kept happening. Guruduttji happened to be in Hyderabad and I happened to be there too.

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman