- Home

- Kabir, Nasreen Munni

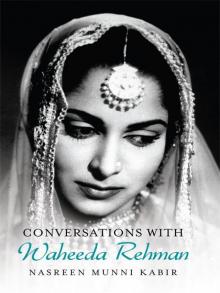

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman Page 7

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman Read online

Page 7

NMK: I didn’t realize you were cast in the film. That would have been interesting.

Coming back to film photography, K3G and most Indian movies are now beautifully shot in colour. But I think it’s a real shame that young audiences are just not attracted to black-and-white films any more. They’re happy to see old song clips on television, but would they go to the cinema to see an old classic on the big screen? This is more or less true of young audiences around the world.

I am sure you will agree with me that the black-and-white film has a more textured and cinematic mood. It also evokes nostalgia and the past.

WR: Things have to change. I like films in colour, but I agree black-and-white films had a more textured atmosphere. Dramatic moments could also be brought out in a far more interesting way.

That said, Dwarka Divecha who photographed Dil Diya Dard Liya, and Fali Mistry who shot Guide did a great job despite the technical limitations of their era. I was lucky to have worked with them and other gifted cinematographers like V.K. Murthy, Jal Mistry, Faredoon A. Irani and Subrata Mitra in Teesri Kasam. They were all excellent and worked well in black and white and colour.

NMK: It is clear that you are very aware of how films are made. Have you ever considered directing?

WR: I had an offer from the Barjatyas once. Some time ago they were planning to ask artists of our generation to direct a film. I said no because I thought it would be hard work. It wasn’t that I was scared of hard work—I still am not. But perhaps I wasn’t confident of doing justice to a film.

I did start to have a better understanding of film-making once I had made my third or fourth film—I knew about frame compositions, camera movements and angles, the different kinds of shots, etc. But all this took time to understand. I think I have a good story sense, and can make constructive suggestions. I know more or less what works and how to make some scenes better. My problem is that I am too logical and Hindi cinema does not bother much about logic.

I remember asking my film directors: ‘How is this scene possible? How can this character do this?’ I always got the same answer: ‘We have to exaggerate and elaborate. If we stick to logic, the film won’t be interesting and it will not run.’

On the sets of Guide. Circa 1964.

NMK: It would be fascinating to see a film directed by you. I have always wondered if actors make good directors because they know the difficulties of performing a scene—how to make it work.

What would a director say to you that was the most helpful when approaching a scene?

WR: I wanted the directors to explain things clearly. I could grasp things very quickly and worked by instinct. But my weak point was my voice. My voice modulation was not very good. Some directors said I spoke my lines too quickly. They would ask me to talk slower and pause at certain points. Otherwise I don’t think they needed to instruct me in detail.

An actor’s voice is very important, especially on the stage, where you must have the ability to throw your voice well. In films you can convey mood—angry, happy or shy—through silent expressions. I am not saying film acting is only about silent expressions because dialogue delivery is important too. But I was well aware I didn’t have a beautiful voice like Meena Kumari or Dilip Saab. They were great actors with great voices and diction.

NMK: Were you ever tempted to act on the stage?

WR: I was very keen. Shashi Kapoor used to run Prithvi Theatre, and I asked him if we could do a play together. He thought it was a good idea, but he was extremely busy. People forget just how popular he was. He made several films at the same time and worked two or three shifts a day—going from one set to another, from one film to another.

In later years, Girish Karnad and Arundhati Nag and others asked me to act in their plays. Now I think what if I am on the stage and forget my lines? Why make a fool of myself?

NMK: When I interviewed Gulzar Saab he said, unlike stage acting, the difficulty for film actors is expressing themselves in bursts of performance. You do a shot, sit down and sometime later you do the next shot. It’s an off-and-on kind of performance.

WR: That is difficult. Plus, when you go back in front of the camera after a break—which could be a long or a short break—you have to match the mood, the intensity and the momentum of your last take.

When I had a difficult scene to do, I’d ask my director to film the whole scene in a master shot, so the emotions would come out in a single flow. Later the scene could be divided into close-ups and wide shots, or whatever.

This was helpful because it allowed us actors to perform the scene from start to finish. Otherwise if we did a shot, sat down, had tea and then went back in front of the camera—the continuity of mood and emotion was gone.

NMK: I hear that Naseeruddin Shah prefers doing a scene in a master shot too. It takes a skilled actor to hold the shot for a long time, especially without having many retakes.

I was surprised when Guruswamy told me in an interview years ago that Guru Dutt would ask for many retakes.

WR: Everyone thought the retakes in Pyaasa were needed because of me, given that I was the newcomer. To the contrary! It was Guruduttji who had this habit of asking for take after take. Sometimes he was not sure what he wanted from a scene. But when you keep retaking the same shot, your performance becomes stale and mechanical. Your dialogue delivery can end up sounding flat and lifeless.

I remember Guruswamy once called me at home—I was not needed on the set as Guruduttji and Mala Sinha were shooting a long dialogue scene that takes place in Mr Ghosh’s office—and he said: ‘Come now! You must see what’s going on. You get worried about retakes—come and watch these veterans. They started the shot yesterday and are still at it.’ [we laugh]

NMK: Even recently, V.K. Murthy in an interview referred to the scene you just spoke about and said that Guru Dutt asked for 104 takes! Clearly he was not easily satisfied with his acting. So how did he judge his own performance?

WR: He would ask his chief assistant or Abrar if his take was okay. Murthy sometimes told him if he thought Guruduttji could do the shot better.

NMK: Did you need many retakes?

WR: My first take was usually good, the second was less good and by the third take my energy level completely dropped. Even if the first take was fine, the directors would invariably say: ‘One more. For safety.’ If you asked the director why—was there something lacking in the performance? What went wrong?—no one would give me a clear answer.

The only directors who explained the need for a retake were Guruduttji, Satyajit Ray, Asit Sen, Vijay Anand, Basu Bhattacharya and A. Subba Rao, the man who made Milan. I made Darpan with him in 1970. These directors explained things clearly to me: ‘Your pitch was too high. Modulate your voice like this.’ Or whatever. But most directors never said anything.

With brother-in-law Abdul Malik (elder sister Shahida’s husband) at Vauhini Studios, Madras, during the making of Rakhi. Circa 1962.

NMK: Some directors do not like showing the actor the rushes—or dailies, as they are also called. During the 1950s, you mentioned the cast and crew saw the rushes and trial shows. Were actors always encouraged to do this?

WR: Yes. And for many years the whole unit would watch the songs too.

After the screening, the director would decide if he needed to retake a shot or a scene, to improve it. Sometimes the microphone boom had dropped into the frame—if it wasn’t very obvious, and just at the edge of the frame, the director would let it pass, but if it had dropped too low into the shot, we were obliged to redo the shot. Sometimes there were problems with unwanted shadows.

If a performance really did not work because the dialogue delivery was not up to the mark, or the emotions were not coming through, the director would film a close-up and insert it into the scene to enhance the drama. We didn’t necessarily refilm the whole scene because the set might have been destroyed by then. A close-up is easy to insert. This process is what we called ‘patch work’.

At the start of the m

ulti-starrer era, the 1970s directors, including Yash Chopra, stopped showing us the rushes because many top stars would create a fuss: ‘Oh, my scene was cut? Why is that?’ Or they would say: ‘I think we should retake the shot.’ They thought they could improve on their performance, even if the director did not think it was necessary.

As far as I was concerned, I told all my directors I wanted to see the final film and did not mind if any of my scenes were edited out.

NMK: For some decades now, actors and directors have been able to judge a performance on set thanks to the video assist [a device which allows a viewing of a video version of the take immediately after it is filmed]. In your time there was no possibility of watching the take until you saw the rushes the next day.

WR: I never liked the idea of looking at the video monitor. I trusted the director. Even when I thought I had given a good shot, I waited for his reaction.

I remember Dilip Saab sometimes commenting on my performance when we were doing a scene together. He would say: ‘Waheeda, you speak too fast. Say your lines a little slower, take a pause.’

NMK: But it sounds like you never feared the camera.

WR: No, I didn’t really because I had made Telugu and Tamil films before working in Hindi cinema. Don’t forget I was used to dancing on the stage before joining films, so the fear and nervousness had long gone.

NMK: In the early 1960s, soon after the release of Kaagaz Ke Phool, you were offered a part in Abhijan, which was released in 1962. The film was based on Tarashankar Bandopadhyay’s popular novel.

How did Satyajit Ray approach you?

WR: The editor of Filmfare, B.K. Karanjia, sent someone to my house with a letter from Mr Ray that said: ‘My leading man Soumitra Chatterjee and my unit believe that you are most suitable for the role of Gulaabi, the heroine of my next film. If you agree to play the part, we’ll be very pleased.’ I was very happy and could not believe Satyajit Ray had thought of me.

A few days later I called Mr Ray in Calcutta and the first thing he said was: ‘Waheeda, you earn a lot of money in Hindi films. I make films on small budgets.’

‘Saab, why are you embarrassing me? It is an honour for me. You have shown me much respect by asking me to work with you. There is no problem about the money. I prefer you don’t mention it.’

(L to R) Sunil Dutt, Satyajit Ray and Nargis at the 1973 Berlin Film Festival where Reshma Aur Shera and Ashani Sanket were screened. Photograph: Waheeda Rehman.

I explained to him that I didn’t speak Bengali, and he said the character he wanted me to play, Gulaabi, is from the Bihar–Bengal border and talks in a mix of Bhojpuri and Bengali. Therefore the language should not be a problem for me. He also added: ‘Remember you can’t come to shoot for four days and then go back to Bombay. We have to film in one stretch, from start to finish.’ I agreed and assured him I’d work out my dates with my Bombay producers.

Soon after our call, I went to Calcutta and met Mr Ray. He gave me an audio tape of my dialogue to make it easier for me to memorize my lines.

NMK: What was your first impression of him?

WR: He had such a towering personality. He had a deep voice and a particular style of speaking.

I was a little nervous at the beginning of the shoot because I was working in an unfamiliar language and, after all, he was a world-famous director with such a huge reputation. But Mr Ray was reassuring and said: ‘I have more confidence in you than you have in yourself. You’ll live up to my expectations.’ I think it was his way of making me feel at ease.

Ray Saab was meticulous and explained everything in great detail. He sketched every scene and made detailed shot breakdowns, even noting the lens he planned to use. His storyboarding was extremely helpful. In those days no one had heard of storyboarding. He was also one of the few directors who gave me a bound script.

There was a scene in Abhijan where I am sitting in a ghoda gaadi [horse carriage] and a sethji is forcibly taking me away. Soumitra [Chatterjee] comes, I look at him and jump out of the carriage and run away. Before Ray Saab could say anything to me, I glanced at the sethji and jumped out. Mr Ray quickly said: ‘I was about to ask you to do just that. But you did it before I could say anything!’

NMK: Do you remember how many months the filming took?

WR: Months? I think the shooting was over in nineteen days. Soumitra had many more scenes than I did and perhaps had to work for a further week or so.

I remember a short scene in which I had to speak some lines, sing and do a little dance—not the Bharatanatyam or a filmy dance—just move my hands as I was talking to the hero. I asked if a song had been recorded for me and Mr Ray said: ‘No, you will sing.’

‘But I don’t know how to sing, and my voice isn’t good.’

He said: ‘We’re used to the voices of Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhonsle, but I want to hear Waheeda’s voice. Gulaabi is a simple village girl, and if her voice isn’t perfect, it will sound natural. That’s the effect I want. You’re forgetting that my films are realistic.’

He told me the entire scene would be filmed in one shot. ‘Come to the studio. Rehearse for a day and then we’ll shoot. You’re a dancer. Why are you getting nervous?’

‘Ray Saab, the dance is not difficult, but I also have to say my lines and convey the emotions—she is sad, she laughs and sings too.’ Soumitra was most reassuring and told me not to worry.

We rehearsed for about four to five hours in the morning and after lunch we finished the scene in two takes.

Satyajit Ray made films the way films should be made—from start to finish. So whether you’re needed on the set or not, you can spend your whole time thinking about your character. It’s not just about learning the dialogue and facing the camera, you must somewhat live the role and not always be acting it.

NMK: Did you ever discuss the possibility of Mr Ray making a film in Hindi?

WR: His wife would ask me to encourage him to do so. When I spoke to him about it, he said: ‘Some day I want to, but then you have all those lengthy songs and dances and all that.’

‘No, make it according to your style.’

I think he was reluctant to make a film in Hindi because he did not know Hindi well and believed that was essential. ‘The most important thing is having command over the language. So I can tell if the actor’s tone is not right. One thing is certain—if I make a Hindi movie, I will cast you.’

NMK: Why do you think Mrs Ray wanted her husband to make a Hindi movie?

WR: Regional films have a smaller reach while Hindi cinema is shown all over India. Perhaps Mrs Ray wanted more people to see his work. His films did well in Bengal, and were occasionally screened in other cities, and people abroad loved them. When he became an important figure in world cinema, then the whole of India started paying more attention to him. But his films were not widely distributed here.

Many years later when he was making Shatranj Ke Khilari, he called me and said: ‘Waheeda, I promised to cast you, but I don’t feel the role in this film will suit you.’

I think the last time I saw him was when he came to Bombay for the dubbing of Shatranj Ke Khilari. He called and said he wanted to come over. He dropped by and we talked for a while.

NMK: I had the pleasure of looking after him during his week-long stay in Paris in 1983, and then met him later in Calcutta. He had a formidable personality and made such extraordinary films. They get better as the years go by.

You say you were lucky to have worked with Satyajit Ray, Guru Dutt, Vijay Anand, Raj Khosla and others. These are precisely the directors who would expect a lot from their actors.

But what kind of roles attracted you?

WR: I wanted to do different kinds of films, and if I was offered the same type of role I refused. It did not excite me to do the same thing over and over again. There is no challenge in repeating oneself because one tends to perform mechanically.

In the 1960s, most Hindi films were light romances. Boy falls in love with girl. Some obstacle come

s in their way, usually created by the parents or a villain, or there is a difference of class between them—the boy is poor and the girl is rich—and ultimately the boy wins the girl.

NMK: I was talking to the director Kalpana Lajmi about your work and she said you always showed a willingness to take chances by choosing atypical roles.

WR: I tried. Some of the films I acted in were not the typical sort. Think of Pyaasa, Mujhe Jeene Do, Khamoshi, Guide or Reshma Aur Shera.

NMK: Another unusual film you made was Teesri Kasam, which was based on a story called ‘Maare Gaye Gulfaam’ by the celebrated Hindi writer Renu. That was the second time you were cast opposite Raj Kapoor after Ek Dil Sao Afsane in 1963.

WR: When I heard Rajji was going to play Hiraman, the hero of the film, a bullock-cart driver, I wondered how he would look in a dhoti. Sometimes you have a strong image of someone and you can’t imagine that person as another personality. I had seen Awara and many Raj Kapoor movies. He was very influenced by Charlie Chaplin and imitated him. Rajji had sad eyes.

With (L to R) sister Zahida, Nargis, Amitabh Bachchan, Sunil Dutt, Vinod Khanna, Amrish Puri and Sukhdev during the Reshma Aur Shera shoot. Rajasthan, 1971.

It turned out that Raj Kapoor was excellent as Hiraman. He had no mannerisms and acted in a natural style. Actually, we were both encouraged not to act in the true sense of the word. The Bengali director Basu Bhattacharya wanted us to perform in a natural style, to give a lifelike performance. Most Bengali directors asked their actors to be natural. They also preferred filming away from the studio on real locations to enhance a sense of realism in their stories. So some scenes of Teesri Kasam were filmed near the Powai Lake, and the rest was shot in Bina, a small town near Bhopal.

Rajji thought the ending of the film should be changed and Hiraman and Hirabai should go away together. But no one agreed to that. The whole point of the story was Hiraman’s ‘teesri kasam’ [third vow]—never to let a nautanki girl travel in his cart again. The writer Renu—who had also written the dialogue for the film—would have been furious if the ending had been changed.

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman