- Home

- Kabir, Nasreen Munni

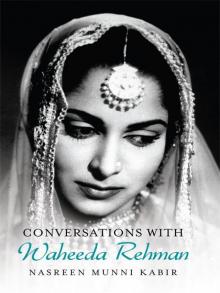

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman Page 8

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman Read online

Page 8

I must tell you about an extraordinary incident that happened at the end of the Teesri Kasam shoot. We had to travel to Bina by train, as there were no flights in those days. When the shooting was over, Rajji, two of his friends, my sister Sayeeda, my hairdresser and I made our way to the station to leave on an early afternoon train for Bombay.

We got on to the train and settled in our air-conditioned compartments. We heard the train engine start and then stop. We assumed it must be some technical problem because again the train started and stopped. Finally, we looked out of the compartment window to see what was going on. The railway station at Bina was very small and on either side of the train we could see huge crowds of students on the platforms. Then we heard people shouting: ‘Utro, utro, dekhna hai, dekhna hai.’ [Get down! We want to see you.]

Someone came and asked Rajji to talk to the student leaders and tell them to calm the crowd down. Rajji opened the door and talked to a group of young men who had gathered near the compartment door. They told him that the local students had wanted to watch the shooting of Teesri Kasam, but were repeatedly given the wrong location address by the production team. By the time they cycled to the spot, having bunked their classes, they could not find a soul there. Apparently, this had happened over many days and so they did not get the chance to see Rajji and me. Now they were very insistent about seeing us.

Receiving the Silver Medal award for Teesri Kasam from President Radhakrishnan in Delhi. 1966.

But Rajji immediately said: ‘You have seen me, but Waheeda Rehman is not coming out.’

‘Why not? We’re her fans.’

He was adamant: ‘No, she won’t come out. She is a woman.’ Rajji’s reply incited them further and they said: ‘So what? She must see her fans or else we will not allow the train to leave the station.’

The situation became very tense. I don’t know what came over Rajji but he dug his heels in and said: ‘No!’ Then he closed the compartment door. That did it! The crowd became furious and started hurling stones and hitting the train with big iron bars. They did not let the train move an inch. We had to duck down in our compartments to avoid being hurt while Rajji was getting more and more enraged. He wanted to go out and confront the crowd. His friends tried to restrain him and, when they realized they couldn’t, they pushed him into our compartment and said: ‘Ladies! Take care of him. He has gone wild.’

And so the three of us—Sayeeda, my hairdresser and I—had to literally pin Rajji on to the seat. I sat on his chest while my sister held on to his legs. He became red as a tomato and tried to wriggle out of our grip while we were struggling to keep him down. We kept imploring him: ‘No, Rajji, no!’ To which he protested: ‘Let me go! Let me go!’ [we laugh]

It became such a drama—but maybe I should say a comedy! In the meantime, our angry fans had wrecked the train. There was shouting and pelting. Finally the police arrived and dispersed the crowd. We somehow got to Bhopal in the early evening and had to wait for hours while the police report and the railway department report were written up.

The next day we arrived at Bombay Central. The people who came to receive us were shocked to see the terrible state we were in. We had fragments of glass lodged in our hair and sprayed on our clothes—we even found bits of glass in our bags.

NMK: It sounds really scary and dangerous.

WR: It was very dangerous. These are also some of the things we go through. Our lives are not always a bed of roses as many people assume.

NMK: But I wonder why Raj Kapoor had such a reaction.

WR: It was strange. I tried to tell him I could stand behind him at the compartment door and so the fans would see me. But he said: ‘No! I have told them no. Why should they look at a woman anyway?’

I said: ‘What do you mean? I am a woman, but I am seen in the movies. That’s my work. Why can’t they see me?’

‘No! They won’t see my heroine.’ He could not be persuaded otherwise. [laughs]

NMK: I suppose when you’re famous and filming in small towns where people didn’t have access to stars, especially in the 1960s, this situation is unsurprising.

You have worked with a number of former Bimal Roy assistants, including Basu Bhattacharya, Moni Bhattarcharjee and Gulzar. How did you meet the Teesri Kasam director?

WR: In the early 1960s, Shailendra, who produced the film, called to say he wanted to come over to discuss a film and brought Basuda to the house. It was Basuda’s first film. They offered me the role of Hirabai and I said no. I had this bad habit of saying no at first. Why? I don’t know. Shailendra said I should sleep over it and then decide. This is what all the producers would say. When he called again, I lied to him saying Guruduttji was starting a movie and I was working in it.

But then Shailendra called Guruduttji who said: ‘Hein? What movie?’ Immediately Guruduttji called me: ‘Did you say no to Shailendra? Why? Don’t you want to earn money to run the house? If you sit at home, how will you manage? And another thing. Why did you lie?’

‘I didn’t know what to do. I lied.’

‘That isn’t good. Shailendra is a very nice person. You must do it. I can’t understand you. This is bad. I think you’re a lazy person.’ [laughs]

Teesri Kasam took a long time in production and was finally released in 1966.

NMK: It was the only film that Shailendra produced and I believe he had a lot of financial problems completing the film.

WR: He had to really struggle hard. One day he came to see me and said he couldn’t pay me. I felt very bad for him. He had tears in his eyes. It is heartbreaking to see a man cry. I told him not to talk about the money.

Shailendra wrote beautiful songs for the film. I loved ‘Sajan re jhoot mat bolo.’

NMK: Your era had the best songs.

You must have met a number of composers over the years, but did you also get to know any of the lyricists?

WR: Sometimes Majrooh Saab visited my sets. He once sent me kebabs when we were in Panchgani on a location shoot.

Once I had to go to Madh Island for the shoot of Girl Friend. My car broke down and so I took a cab. When I got there the director was upset with me and said I should not have risked travelling all that way alone in a taxi. I told him I didn’t want the shoot to get delayed.

I don’t know how but Majrooh Saab heard about this incident, and when we met a few days later, he said: ‘Bibi, never do that again. Damn the shoot! Do you realize what a desolate and lonely place Madh Island is? And you went there alone in a taxi? Don’t show so much dedication! Next time, phone me and I’ll send you my car.’

And of course I met Shailendra many times during the making of Teesri Kasam.

NMK: I once interviewed Dev Anand about how he chose Shailendra for Guide rather than Sahir Ludhianvi, who was the Navketan favourite. Dev Saab said he happened to meet Shailendra on a flight and he expressed his desire to work on Guide. Dev Saab readily agreed because apparently Sahir and S.D. Burman were not getting on well at that time. Shailendra’s songs were indeed superb in Guide, this key film in your career.

Visiting Dev Anand on the sets of Prem Pujari. Circa 1969. Waheeda Rehman made the maximum number of films (seven) opposite Dev Anand.

Were you familiar with R.K. Narayan’s novel before starting the film?

WR: It was Mr Ray who asked me to read the novel because he was considering adapting it. He told me if the film ever took off, he would cast me as Rosie. She had to be a good dancer and he knew south Indians were usually good dancers, and so he had thought of me.

I had forgotten all about it when a year or two later Dev told me he was producing the film. I asked: ‘You mean R.K. Narayan’s novel? But isn’t Mr Ray making it?’

Dev said: ‘No, no, I know about that. I have bought the rights of the book.’

Satyajit Ray would have conceived the film in a completely different way. But I believe I was fated to play Rosie, no matter who was going to direct the film. Many actresses were keen to play Rosie, including Padmini and Leela

Naidu. They sent me letters saying I should let them know if for any reason I did not accept the part.

NMK: I never knew Mr Ray wanted to make a film based on R.K. Narayan’s novel. That will be a surprise to many. Yet he clearly thought the role of Rosie was perfect for you, just as no one but Nargis could have played Radha in Mother India.

WR: Or Meena Kumari as Chhoti Bahu in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam.

NMK: Absolutely right.

You seemed to suggest there was a possibility that you might not have played Rosie. Is that right?

WR: I almost didn’t, because Dev announced that Raj Khosla was going to direct. I said: ‘Dev, have you forgotten how we quarrelled during the making of Solva Saal?’

‘Forget it, my friend. Everyone fights in life. Come on now, Guide is a very big picture, Waheeda. It is going to be made in English and in Hindi. Don’t be like that. You are a mature person and Raj has changed.’

I don’t know what happened but in the end Dev decided against Raj Khosla as director.

NMK: What was your disagreement with Raj Khosla? Was this during the making of Solva Saal?

WR: That’s right. You see in the film I play a naive sixteen-year-old girl who is in love with a boy who promises to marry her. We elope and foolishly I take all my dead mother’s jewellery with me. We catch a train and, halfway through the journey, the boy steals the jewellery and disappears. I am distraught and decide to commit suicide. I get off the train and head towards the sea. Dev, a co-passenger, has been watching me all the while and has understood the whole situation. He follows me and saves me from drowning.

Our clothes are wet, and so we go to a nearby dhobi ghat and the dhobi lends us some clothes till our clothes have dried. What do I see? The costume department gives me a chiffon sari and a strapless blouse. I looked at Raj Khosla and asked: ‘Rajji, am I going to wear this?’

He said: ‘I know you! Try it, but if you don’t feel comfortable, wear whatever you want.’

So I went to my make-up room where my mother was sitting. I put on the sari and the strapless blouse and looked at myself in the mirror. ‘I can’t wear this.’ I took the blouse off and put on another blouse with sleeves. When I returned to the set, Raj Khosla saw me and lost his cool. ‘You don’t listen to your director. Who do you think you are? Madhubala? Meena Kumari? Nargis? Only two of your pictures have been released, and you want to have your way.’

He reminded me how I had insisted on keeping my name when I first signed the contract with Guru Dutt Films, and the fuss I made about the costumes in C.I.D. But I said: ‘Rajji, you told me if I didn’t feel comfortable, I didn’t have to wear this blouse. It didn’t feel right.’ Dev then turned to me and asked: ‘Waheeda, what’s the problem? What difference does it make?’

I explained to Dev: ‘In this scene the hero asks me my name and I say it is Laajwanti [bashful/shy]. And he says: “Tabhi toh itni laaj aati hai.”’ [That’s why you’re so shy.]

If this is the dialogue in the scene, I asked Raj Khosla, would this shy sixteen-year-old wear revealing clothes in front of a man who is an utter stranger at that point of the story? He said: ‘Oh, now you are talking about logic. Is this your counterargument?’

‘I think it would be amusing if we were given baggy, ill-fitting clothes and looked like clowns. That would create a moment of comedy.’

‘Lo ji, now she’s telling me how to direct.’

Raj Khosla decided to wrap for the day. The next day we returned to the set. Everyone had calmed down. I wore a different blouse and we carried on shooting.

NMK: You had a point. If the girl is called Laajwanti, her name assumes an innocent sort of character and revealing clothes would have been inappropriate.

I must say I really liked Solva Saal. It is a charming film and Raj Khosla directed it beautifully. Interestingly, there isn’t a hint of tension in your performance.

Did you ever work with him again?

WR: After my two children were born, Amarjeet, Dev’s good friend who made Hum Dono, was producing a picture called Sunny. He was going to introduce Sunny Deol in it and offered me the role of the mother. I agreed and then Amarjeet quickly added: ‘Now you’re married and have children. Time has passed. I have to tell you—Raj Khosla is the director.’

When I told my husband, Shashi, about the offer, he said: ‘Come on, grow up now. It doesn’t matter if you argued in the past. Do it. It isn’t right to say no.’ I said yes to Amarjeet and played the mother’s role in Sunny.

Raj Khosla was a very good director. He filmed songs very well. We had our arguments, but he was a very nice person to spend time with. He was a cheerful fellow. Guruduttji was quiet and Raj Khosla was the lively one. In later years, when we both became more mature, we put all our differences behind us.

NMK: Coming back to Guide, what happened after Raj Khosla was dropped from the project?

WR: Chetan Anand started work on the Hindi Guide, and the English version was the American director Tad Danielewski’s responsibility. At first neither of them wanted me as Rosie. By that time, I wasn’t sure I wanted to do the film either. But Guruduttji sent word through Murthy that I must do it.

When the shooting began there was a clash between Tad and Chetan Saab almost immediately. They both wanted different camera positions, and the lighting took hours.

NMK: Do you mean to say you filmed a scene in Hindi and then shot the same scene in English?

WR: That’s right. They needed to save money. Both language versions had the same sets and the same locations. That’s how we worked. But it wasn’t happening. Tad and Chetan Saab had their egos.

It wasn’t long before Dev came to my make-up room and said: ‘Waheeda, see how much time they’re taking. One says put the camera here, the other says put it over there. Tad wants one action and Chetan Saab another. And their endless discussions! I think we should first finish the English version then think about the Hindi Guide.’

That’s what happened. We first completed the English Guide and when it came to the Hindi Guide, Dev asked Goldie [Vijay Anand] to take over. I knew Goldie from the Kala Bazar days. He wrote excellent dialogue.

NMK: How did you like working with Tad Danielewski? He was the only American director you worked with.

WR: Tad was very vague. Whenever I asked him anything, he would say: ‘Maybe, maybe.’

You can say that sometimes, but not all the time. You need the director to be clear. Should Rosie react warmly? Or should she react coldly?

NMK: You mean the director has to be decisive and bring out shades of the character’s behaviour?

WR: Yes. Saying ‘maybe’ doesn’t help. Goldie would explain precisely how the scene should be played. You can get angry or upset with a director, but he must be clear. Satyajit Ray was very clear—it was either yes or no.

With Kishore Sahu and Tad Danielewski, the American director of the English Guide, on location at the Elephanta Caves. Circa 1964.

Acting is an understanding between actor and director. Performance comes from that combination of minds. I may actin a certain way, but the director might feel it is too much and will suggest lowering the pitch or what needs doing to enhance the performance. The director must be clear about the tone of the scene and Tad was vague.

NMK: The Nobel Prize–winning novelist Pearl S. Buck wrote the English screenplay of Guide and I believe that was the only screenplay she wrote.

Was your English dialogue dubbed by any chance?

WR: No. I spoke my own lines. I practised them with Pearl S. Buck. She was a very interesting woman. One day she told me: ‘Some people may want you to speak in an American accent; don’t do that. As long as your lines can be understood, that’s all we want. I’ll correct you if something isn’t right. Don’t be self-conscious. If you make a mistake, we can dub it later. Just talk naturally. The film is being shot in India, the story is Indian and, most importantly, the characters are Indian. They’re not Americans working in India, so why should Rosie speak in an American accent

? It will sound odd.’

NMK: Did you think Rosie was a bold character for the time? Did she break with social norms?

WR: Many people told me I was making a mistake by accepting the role. ‘You’re shooting yourself in the foot. This will be your last film.’ There were many reasons for their concern. The first being that when the audience is introduced to Rosie they discover she is a married woman. And a heroine in a Hindi film must be unmarried so that the hero can fall in love with her. On top of that, Rosie leaves her husband and goes off to live with Raju the guide. But they do not marry. This was very bold. Unmarried couples did not live together at the time, and definitely not in Hindi cinema.

(Standing, L to R) Personal hairdresser Mrs Solomon, assistants John Anderson, Prabhuji Jasbir and actor Anwar Hussain. (Sitting) Satyadev Dubey and Pearl S. Buck. Photograph taken by Waheeda Rehman during the filming of the English Guide. Udaipur, 1963.

I give full credit to Goldie. He treated the story so beautifully and in such a dignified way. The relationship between Raju and Rosie never seemed cheap. In some Hindi films, the other woman is called a ‘rakhail’ [mistress] and is portrayed as a vulgar person, more of a vamp type. But Goldie portrayed her in a modern and decent light.

NMK: You’re right. Rosie was not at all depicted as an immoral character and is totally unlike the stereotypical heroine of Hindi cinema. She makes her own decisions, is brave enough to refuse to stay in a failed marriage and is unwilling to continue her relationship with Raju when it turns sour.

WR: Exactly! She slaps her husband and walks out on him. A wife reacting like that was never seen in Hindi films. And as you said, when she realizes that Raju is behaving badly—drinking and gambling and using her—she has the courage to walk out on him too.

The characters in Guide behave like grown-ups. They believe in mature relationships. Rosie leaves her husband and leaves Raju as well. Their relationship actually starts out of sympathy and only gradually develops into love.

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman